Ali e Vele

Wings and Sails

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

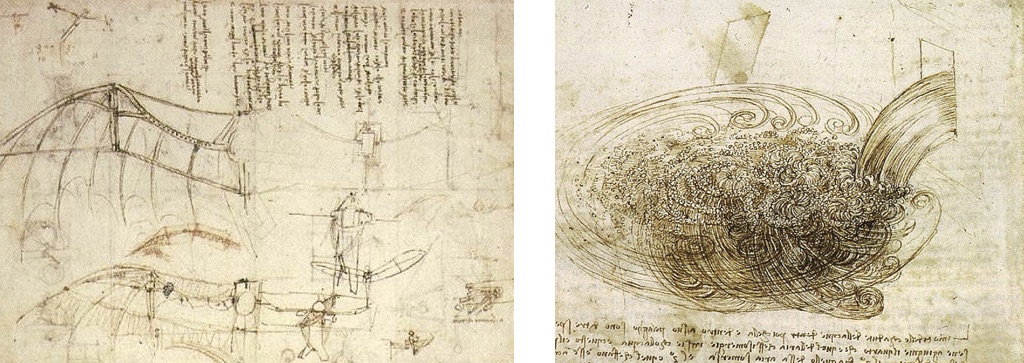

Studio di ala, Codice sul volo degli uccelli, Biblioteca Reale, Torino

Studio del moto turbolento, Codice Atlantico, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milano

.

Pensate allo splendido volo planante di un gabbiano: la forma delle sue ali è tale che per la leggi della Fisica il flusso dell’aria genera una forza di sostentamento. La vela è un’ala verticale che, data la sua angolazione rispetto all'asse della barca, produce una forza con una componente nella direzione del moto, anche controvento. Come contrastare efficacemente la componente trasversale e quindi lo scarroccio? Con un’ala, piatta tuttavia, subacquea: la deriva. La bellezza semplice e pura della vela implica l'evitare il fenomeno fisico caotico detto "turbolenza", come vale anche per il volo di uccelli e aeroplani. La turbolenza è stato osservata per la prima volta con occhi di scienziato e artista da Leonardo da Vinci.

Think about the splendid gliding flight of a seagull: the shape of its wings is such that by the laws of Physics the airflow generates a lifting force. The sail is a vertical wing which, given its angle with respect to the boat axis, produces a force with a component in the direction of motion, also upwind. How to deal effectively with the transverse component to contrast the leeway? With an underwater wing, however flat: the drift. The simple and pure beauty of sailing implies to avoid the chaotic physical phenomenon called "turbulence", as also holds for the flight of birds and airplanes. The turbulence was first observed with the eyes of a scientist and artist by Leonardo da Vinci.

Vela e moto dei fluidi

Sailing and motion of fluids

La Fisica della Vela coinvolge principalmente la Dinamica e il Moto dei Fluidi: aria per le vele, acqua per la parte sommersa (la cosiddetta “opera viva”. E’ su quest’ultimo che ci soffermeremo, dato che rappresenta l’aspetto più complesso e anche interessante. Ci riferiremo in particolare alle vele.

La spinta fornita dalle vele è massima quando l’aria scorre lungo di essa regolarmente. Se potessimo visualizzarne la velocità, vedremmo che essa varia con continuità in grandezza allontanandosi dalla superficie della vela, pur mantenendo la stessa direzione. E’ il cosiddetto moto “laminare”, in cui l’aria scorre come se vi fossero dei sottili strati d’aria paralleli con velocità leggermente diversa. Esso è segnalato da fettucce segnavento disposte orizzontalmente, lungo la direzione della velocità dell’aria rispetto alla vela.

Una spinta in avanti proviene dalla curvatura del flusso dell’aria, indotta dalla curvatura della vela (l'arte del velaio): la curvatura implica una accelerazione centripeta e quindi una forza (F = ma). Una forza nella direzione opposta agisce sulla vela e lo spinge in avanti.

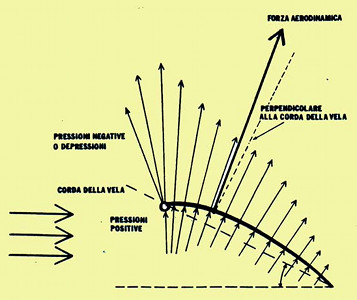

Una ulteriore spinta viene dalla maggiore velocità dell'aria che scorre dietro la vela, a causa del percorso più lungo che essa deve seguire. Secondo l'equazione di Bernoulli, la velocità più elevata si traduce in una pressione inferiore. L'effetto differenziale può essere visto come una depressione che "risucchia" la vela dalla parte posteriore rispetto alla direzione del vento. L'ala di un aereo ha un profilo quasi piatto inferiore, per cui l'effetto dominante è un suo risucchio dall'alto.

La figura a sinistra mostra le forze che agiscono sulla vela: le forze provenienti dalla pressione e, sul suo lato posteriore, le forze totali risultanti dall'effetto di risucchio aggiunto. Una dimostrazione pratica dell'effetto risucchio è illustrata nella figura a destra.

Le differenti velocità di scorrimento tra strati adiacenti implicano delle tensioni di attrito tra di essi. Il moto resta laminare finché esse sono abbastanza piccole da essere assorbite dalle seppur minime forze di coesione tra le molecole dell’aria. Quando le tensioni diventano eccessive, è come una corda che si rompe: il moto laminare si rompe e il moto diventa disordinato, “turbolento”. E’ il moto che per primo Leonardo da Vinci ha osservato con occhi di scienziato e ha rappresentato in uno dei fogli del Codice Atlantico (vedi la figura in testa pagina).

Quando il moto diventa turbolento, le fettucce segnavento applicate sulla vela non sono più sostenute da un regolare flusso dell’aria, si afflosciano. La forte spinta sulla vela non c’è più: nel moto laminare le molecole dell’aria spingono tutte nella stessa direzione, ora si comportano in modo incoerente. E’ per l’insorgere del moto turbolento che la randa è meno efficace con vento in poppa che al traverso o di bolina: la spinta diventa di piatto e non per effetto di curvatura. Bisogna ricorrere a vele speciali, con una curvatura tale da assicurare un più regolare scorrere dell’aria, è il momento di issare un gennaker o uno spinnaker.

Per la sua natura disordinata, il moto turbolento è inadatto a un calcolo analitico e difficile da trattare anche con metodi numerici tramite i potenti calcolatori di oggi. Il ruolo di intuizioni, prove, “magie” diventa importante, da cui tutto il mistero che viene mantenuto su vele e derive di barche per grandi competizioni veliche e, per moti analoghi motivi, sulle soluzioni aerodinamiche per le vetture di Formula 1.

E’ disponibile una ampia letteratura specificatamente sulla Fisica della Vela, anche a livello molto avanzato, soprattutto proveniente da paesi in cui la Vela è un culto nazionale. Del materiale è disponibile in rete.

The Physics of Sailing involves mainly the dynamics and the flow of fluids: air for sails, water for the submerged part. We focus on the latter, since it represents the most complex and also interesting aspect. In particular, we will refer to the sails.

The thrust provided by the sails is maximal when the air flows along them regularly. If we could visualize the speed, we would see that it varies continuously in magnitude moving away from the surface of the sail, though maintaining the same direction. It is the so-called "laminar" flow, in which the air flows as if there were thin parallel air layers with slightly different speed. It is denoted by wind indicators horizontally oriented, along the direction of the air velocity with respect to the sail.

A forward thrust comes from the curvature of the air flow, induced by the curvature of the sail (the art of the sailmaker): the curvature implies a centripetal acceleration and hence a force (F = ma). A force in the opposite direction acts on the sail and pushes it forward.

An additional thrust comes from the higher speed of the air flowing behind the sail, which is due to the longer path to be followed. According to Bernoulli's equation, the higher speed results in a lower pressure. The differential effect can be viewed as a depression, which "sucks" the sail from the back with respect to the wind. The wing of an airplane has an almost flat lower profile, so that the dominant effect is a sucking from above.

The left figure shows the forces acting on the sail: the forces coming from the pressure and, on the its back side, the total forces resulting from the added sucking effect. A practical demonstration of the sucking effect is shown by the right figure.

The different speeds of adjacent layers imply tensions of friction between them. The flow remains laminar until they are small enough to be absorbed by even minimal cohesive forces between the molecules. When the tensions become too large, it is like a rope that breaks: the laminar flow breaks up: the flow from regular becomes chaotic, "turbulent". It 's what Leonardo da Vinci first observed with the eyes of a scientist and has shown on of the sheets in the Codex Atlanticus (see the figure at the top of the page).

When the flow becomes turbulent, the strips on the sail acting as wind indicators are no longer supported by a regular air flow, they fall down. The strong thrust on the sail is gone: with laminar flow all air molecules push the sail in the same direction, now they behave incoherently. It’s because of the onset of turbulent flow that the mainsail is less effective downwind than crosswind or upwind: the pressure becomes flat and not as a result of curvature. Special sails are required, with a curvature so as to ensure a smoother flow of air, it's time to hoist a gennaker or a spinnaker.

By its chaotic nature, the turbulent flow is unsuitable for analytical calculations and difficult to treat even with numerical methods through the powerful computers of today. The role of intuitions, of testing, of "wizardry" becomes important; from this all the mystery that is maintained on the sails and on the keel of boats for sailing competitions and, for similar reasons, on the aerodynamic solutions for Formula 1 race cars.

A good literature is available specifically on the Physics of Sailing, also of advanced level and especially from countries where Sailing is a national cult. Material is available online.